The world’s energy systems and markets have taken a massive shock in the last six months with the war in Ukraine, with the supply shortages and high prices are incurring a massive toll on industry and consumers alike across UK and Europe, Scandinavia, and as far away as Australia. But as an essential input into every economy, these extreme prices leave us wondering where all the money is going, and whether our perhaps naive energy market concepts have opened us up to material sovereign risks.

International participation is becoming impractical

With governments across Europe having to dig into their pockets to the tune of 2 Trillion dollars to subsidise the nearly then fold increase in energy prices, everyone is trying to trace where the money going, and what powers governments have to claw it back in times of crisis like we are in now. With global energy contracts and derivatives being even more complex than the credit derivatives that crashed markets in the GFC, it is a monumental task to try to unpick these contracts for the hope of being able to apply windfall taxes to the profiteers. Of course, that only applies if these companies are subject to sufficient jurisdictional powers in the first place.

In Australia, this has become incredibly obvious as the price of gas on the east coast pushes 5 times higher to match the demand of gas in Europe, even though the cost of production has barely changed. What’s more, the suppliers of gas are not bending to allow reservations for the local market, citing sovereign risk (i.e their investment returns) as the reason that governments should not be allowed to intervene.

Energy security has always been an issue of national interest, and being reliant another nation or foreign company in any manner for the supply of energy at a reasonable price, becomes a major problem when the chips are down.

In the same way that Germany can no longer rely on Russia for the reliable supply of gas, Australia can no longer rely on offshore multinational oil and gas companies to provide energy at a reasonable price. As the energy transition to renewables continues to rely on oil and gas for the next twenty years, we must ask ourselves whether the risk to our sovereignty is worth the “efficiency” of open markets and international participation.

The dark secrets of merit order

Even amongst the chaos of fossil fuel prices hitting the roof around the world, one would presume that our ever growing fleets of renewable energy should be keeping prices down. But in many wholesale markets with over 50% renewables running at any point in time, strangely our energy price isn’t as cheap as we might expect. Surely the price of renewable energy isn’t correlated to the price of gas?

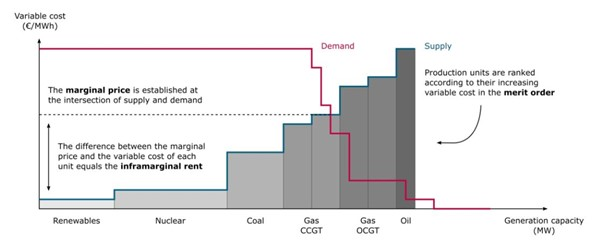

Unfortunately, due to the way that we have designed and built our energy markets, we have coupled the price of the two energy sources. The market “merit order” approach in most spot markets around the world typically sets the price for a particular time interval at the maximum price in the list of generation that is needed at at time. This means if 95% of the bids are renewables at $80 per MWh, and 5% is for gas at $300 per MWh, then the price is paid out to all generators at $300 per MWh for that time interval. In theory, this “inframarginal rent” is meant to cover long term marginal costs. In a commodity squeeze, it becomes a windfall profit.

The consequence of this is that the extreme price payments of gas and coal due to commodity shortages in Europe are being propagated to all markets coupled to the international price, regardless of their input costs – gas, hydro, wind, solar or nuclear – which is why we are not hearing much criticism coming from the renewables sector who are typically up in arms over profits to oil and gas companies. But as a result, it is extremely hard to unwind and to apply windfall taxes to just oil and gas companies alone.

But ultimately it is customers that are footing the bill. Even if governments do step in, as they have in UK, France, Germany and Scandinavia, the magnitudes of the funding is eye watering and not sustainable in any economy. This is the real sovereign risk posed by the continuation of today’s energy markets.

Cybersecurity and energy security

This energy crisis is all taking place with the backdrop of increased geopolitical tensions in Europe and Asia, and a dramatic increase in cyber attacks on corporates, governments, and critical infrastructure. Whilst we becoming more diligent within our own borders to ensure we better protect our assets from outside attacks, there are growing parts of our energy system that are more dependent than ever on foreign companies “doing the right thing”. Unfortunately, recent global politics recently has taught us that this is no longer a valid assumption.

Moving towards 100% renewables in 15 years, it is not unreasonable to see risks coming from any sort of reliance on foreign companies and national actors for operating our energy system. That means overseas supply chains for commodities such as oil and gas, for the manufacturing of key equipment such as solar panels and turbine blades, and for IT systems and data centres situated around the world. These have the potential to become energy security risks – something we are less familiar with given our abundance of natural resources.

The $200 billion dollar question

Even two years ago, I think most experts in the energy sector would have said that government intervention in energy markets is too expensive, and not worth the risk of even the worst possible outcomes. With European nations now writing cheques for $200 billion dollars to sustain the system for another 18 months, we can see that the impacts of a crisis are massive, and with no real end in sight.

Pausing or capping our energy markets is an administrative nightmare, but at the same time within the control of governments. In Australia, both electricity and gas markets have been put into administered pricing for periods already this year. The real challenge is to question that when we restart them, do we expect a different outcome? Price shocks like these are likely to be with us through the entire transition, so we should do the sums to know if we can really afford them.

So in Australia, a nation rich in commodities and with no underlying energy sovereignty issues, we find ourselves more vulnerable to global market forces than we are comfortable with. And we will need our governments more than ever to help manage these risks – to hold Adam Smith’s hand as we walk through a veritable minefield of risks on the path through to 100% renewables.