So I want to talk about autonomous cars, but really underneath I want to talk about our journey discovery in the domains of AI and autonomy, and autonomous cars happens to be our current focal point.

My journey in autonomous systems design

But first, a bit of my history in AI, and how I’ve seen it evolve over the last 30 years.

I’m a Gen Z, born in the early 70’s, of a generation that has been at the pivot point of the massive digital transition. From simple digital watches and calculators that got us to the moon and back, to the shrinking of mainframes down into laptops, and the tectonic shift from academic bulletin boards to the full-blown internet age – we’ve witnessed an incredible evolution in the last 50 years. As a young child, I wrote my first program in BASIC on an Apple 2e computer to compute basic trigonometry for working out wind vectors. Then later as an engineering Ph.D. student in the 90’s, I worked on control and navigational systems for semi-autonomous drones, where we used first generation AI technologies (neural networks) to realise robust, and adaptive control systems that could diligently follow around pre-set navigation exercises. But by that point in the mid 90’s, we had hit the ceiling of our understanding on what it took to reach full autonomy. We had the basic tools of machine learning – feedforward and recurrent neural networks, reinforcement learning, and so on, but this was very much labelled as narrow AI, and not really the same stuff that would be required to make decisions, and exhibit complex goal oriented behaviour.

The next 10-15 years up until 2010 was quiet period for machine learning and AI. Sometimes this period is referred to as the second AI winter, but in many ways it was an opportunity for the theory to catch up to the spooky practices of neural architectures. Over that period, our understanding of humans make decisions moved from the analogies of the mind as computers (i.e. Turing machines, see John Anderson, Gerry Fodor), and more towards an incredible collection of heuristics that are very effective in different contexts. Philosophers got past the dichotomy between connectionist and symbolic architectures, and past the subjectivity aspects of the human experience (see Chalmers and the “hard problem”). Suddenly, the collective wisdom become that a collection of narrow AI systems working together is what humans do, and if we can make a machine exhibit complex goal directed behaviours in this way, then perhaps they were on were on the right path to full autonomy after all.

Now in 2022, the scientific fields of advanced control (autonomous systems and robotics), artificial intelligence and machine learning, and cognitive and decision sciences have completely converged. On top of that, we have almost unlimited computational power at our fingertips. We have robots that can dance to R&B and do parkour, we have cars that can drive themselves around San Francisco without hurting anyone, and have drones that can take out enemies in foreign countries.

Where is autonomous technology at today?

So, putting aside the science fiction for a second, where are we really at in the tech cycle today? What is evident to me is that each of these steps towards full autonomy builds on the previous one; from basic digital infrastructure, to embedded software, to offline search / simulation based design optimisation, to real-time sensing and multi-goal inference and optimisation, and finally to symbolic understanding, reasoning and goal orientation. They are all layers towards achieving more and optimised outcomes, or efficiency plateaus, with each layer depending on their preceding layers of innovation.

We have reached the stage where machines or systems can now exhibit complex, goal directed behaviour; that is, they can robustly perform goals that have been set by humans. They cannot yet reason what those goals should be, or whether they are a good idea or not, but nonetheless they can achieve these outcomes and meet the myriad of constraints put in their way.

The next frontiers in autonomy – the next layers in the cake – will be about setting complex goals, how we communicate and share these goals with machines and systems to make sure they are doing what we want them to do. Equally important is the converse – we want machines and systems to communicate with us, to explain what decisions they are making, and why.

From electric vehicles to autonomous vehicles

With the much needed arrival of electric vehicles, we’ve all started to drink the silicon valley cool-aide on EVs and the inevitable technological shift to autonomous vehicles (AVs). There’s no doubt about it – they’re cool – and a great landmark of human achievement. But we didn’t really consider them feasible without first inventing the digital car, otherwise known as electric vehicles. Cars needed to become digital first, with digital engines and energy sources, equipped with the right sensors, and with displays and speech enablement to communicate goals and safety issues with drivers.

However, whilst we are heading in the direction of AVs, it is highly unlikely that we will see every part of the transport sector, or every car on the road, transition to full autonomy in any uniform manner. There are different value drivers and goals for each industry segment, and even for different individuals. Some will see the value of having a fully autonomous vehicle for the added price of $20,000 (see Telsa FSD), some will be content with a less sophisticated, manually operated or supervised driving solution. But this non-uniformity is actually reflective of strong alignment with human goals – meeting individual needs, yet immensely diverse.

But there also seems to be a ceiling when it comes to high risk environments. The aerospace sector has pioneered the automation and control domain for 50 years. It’s taken people to the moon without astronauts having to lift a finger, so it was undoubtedly an immensely powerful shift in technology. But still today, we persist with human pilots to improve the safety, reliability and humanity in-the-loop of air transportation. Likewise in the military sense, drones are used to reduce risk for pilots flying into unsafe airspace, but humans are still ultimately responsible for decisions to fire on targets, for better or for worse. We can liken this as a glass ceiling in our push for full autonomy in cars, with most settling for Level 3 autonomy (driver assisted, or advanced cruise control) as the technology that maximises benefit. Recent studies have to indicated that the average German households will adopt Level 3 technology in 10 years, and are not likely to adopt full autonomy for another 20 years (see Weigl paper).

Why is it taking so long?

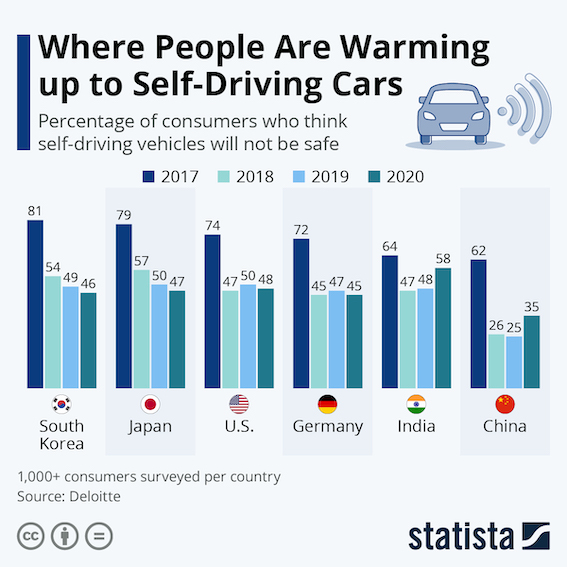

Its close to nearly a decade since the autonomous vehicle buzz first hit the bay area. But time drags on, there are more people asking questions (see Guardian article) about why is it taking us so long. The answer, not surprisingly, is about our journey with artificial intelligence, and also our well founded fears of systemic risk. Killing people is bad for brands (e.g. Uber and Facebook’s self driving car programs). But also we need the social license from consumers to accept the new technology, which is slowing changing around the world.

To be as good as a driver, a car will need to imbue a form of general intelligence. Today we only really have narrow AI, and the ability to do only very specific tasks very well. When these systems are faced with uncertain circumstances, they do not have the resilience, the generalisation capacity and the repertoire to make sound judgements. Whilst we will likely get there with enough time, there is still a nagging question whether we want to hand over the controls to algorithms that are not yet proven to be more competent drivers than ourselves.

So whilst autonomous cars are indeed coming, and progression along driver autonomy scale (levels 1 -5) are the next few evolutionary steps, they are much more likely occur once the base enabling technologies (electric vehicles, navigation systems, sensors, etc) are sufficiently advanced into the mass market. AVs will likely appear at first in niche applications, such as food delivery and ride services, and then perhaps in the luxury car market due to their high cost.